Provision advanced imaging technology machines will be deployed as a layer of security at airports. It uses ses low-level radio waves in the millimeter wave spectrum. Two rotating antennae cover the passenger from head to toe with low-level RF energy, according to the American College of Radiology.

Business travelers have many other priorities such as on time travel, safe transport of luggage and shorter screening times. So it’s more likely that airport screening privacy concerns about body scan images at airport security falls lower on the wish list.

Yet, after the attempted bombing of a 2009 Christmas flight from Amsterdam to Detroit, MI, privacy advocates seemed to have gained an unbalanced amount of attention to express their disapproval of the expanded use of full body scanner technology by the U.S. Transportation Security Administration (TSA). That criticism is weak. The use of imaging technology for screening is optional, and privacy concerns have been addressed previously.

Two types of airport body scanner technologies exist: millimeter wave – relies on radio frequency energy (L3 Provision, Woburn, MA), and backscatter – uses low level x-rays (Rapiscan Systems, Hawthorne, CA). According to the TSA, both are safe. And the standard use of x-ray technology for body scanners is well within acceptable levels, according to the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements (Commentary No. 16, December 2003), Bethesda, MD.

X-ray scanning is already used to inspect baggage, parcels, cargo, vehicles, industry and mining equipment. And people are scanned for security reasons at many different sensitive locations.

It’s important to realize that only 40 millimeter wave machines are currently for airport screening at 19 airports in the U.S., so this technology is still new and in limited in use.

Rapiscan 1000 Secure single pose imaging machines will be deployed as a layer of security at airports. It uses extremely weak X-rays delivering less than 10 microRem of radiation per scan ─ the radiation equivalent one receives inside an aircraft flying for two minutes at 30,000 feet, according to the American College of Radiology.

Rapiscan 1000 Secure single pose imaging machines will be deployed as a layer of security at airports. It uses extremely weak X-rays delivering less than 10 microRem of radiation per scan ─ the radiation equivalent one receives inside an aircraft flying for two minutes at 30,000 feet, according to the American College of Radiology.

In the fall, the TSA confirmed its procurement plan to acquire an additional 150 backscatter units. TSA spokesperson Sarah Horowitz says that there are funds to purchase an additional 300 imaging technology units, but a deployment schedule has not been finalized.

Let’s consider the challenge handled by the TSA: more than 620 million passengers traveled domestically in the U.S. between November 2008 and October 2009 plus another 88 million traveled internationally during that time, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. These travelers passed through approximately 1,580 metal detectors nationwide.

When airport security is heightened – and additional security measures have been put in place at U.S. airports, business travelers and others are more concerned about long waits at security checkpoints and whether the resulting delays may impact flight schedules.

Advocacy should be focused on how much additional time imaging technology requires vs. the current use of metal detectors. Horowitz says the TSA is in the process of evaluating which checkpoint configurations will allow optimal screening.

On a positive note, if it takes a few seconds longer for screening, maybe it will help pace the flow of passengers to avoid the current bottleneck when people grab at their personal belongings after the checkpoint. How many times have you been elbowed by someone else as they try to quickly put on their shoes or while they repack their items out of the plastic bins?

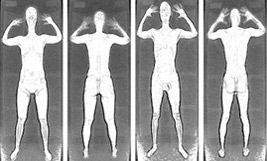

Millimeter wave technology produces an image that resembles a fuzzy photo negative.

Since December, expanded airport screening measures for inbound international travelers to the U.S. have required added security, including manual “pat-downs” and inspections of all carry on baggage at flight gates – sometimes delaying departure by three hours or more. Do people really think that a 3D image is the airport security problem that should be the focus?

As long as security cameras are turned on and the tapes are being saved, most travelers assume either limited or a total lack of privacy as soon as they approach the airport.

The TSA has explained that images from the full body scanners are immediately destroyed. Is that the best approach? That is, if someone were to bypass screening with an undetected substance or weapon, wouldn’t we want to have the historical records checked to find out who made the error? Should scans remain active for 24 to 36 hours – enough time for investigators’ review if ever needed?

Because the privacy issue for full body scanners is of little consequence, perhaps travelers are expressing their annoyance with airport security measures that tend to change reactively based on the latest threat?

Backscatter technology produces an image that resembles a chalk etching.

Take off your shoes. Remove your laptop. Remember, 3-1-1. Comply with the extra pat-down. Open your carry on luggage for search. The latest: please stand within or next to the full body scanner and hold your arms up.

Of course, the recent TSA checkpoint blunders at New York City regional airports haven’t inspired greater confidence, either.

Business travelers care about their experience at the airport, but having their privacy invaded by a body scan isn’t first on their list of concerns.